Route 66 is a 2500-mile open air museum. It reminds me of some of the great open-air museums we have visited, such as Beamish Museum in England, Upper Canada Village in Canada, and Colonial Williamsburg in the US. It is less “authentic” than those sites in the sense that the old bits are scattered among all the new bits and no one authority curates or preserves it. It is not frozen in time the way that these more formal museums are. It is subject to development and change and preserves and expresses different periods in different places.

But the Route 66 experience is in some ways more authentic than that of the formal museums. You are not shopping in the shops at Beamish, nor digging coal in the mine or catching a train at the railway station. You are not grinding grain in Upper Canada Village or forging horseshoes in Colonial Williamsburg. At best you are watching reenactors do it. But on Route 66 you are doing what everyone who ever drove Route 66 was doing. You are driving to a real destination with the real, if tarnished, allure of California. If the trek is less arduous than it was for the Joad family in The Grapes of Wrath, it is still a trek. It still requires stamina. You are still following the Mother Road for real, and I can’t think of another outdoor museum that really gives you the opportunity to do the thing for real the way Route 66 does.

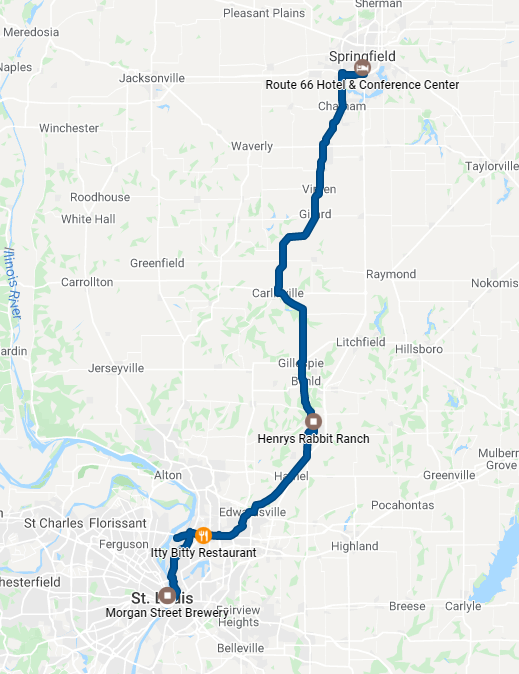

On this day, May 1, 2018, we take a fairly short drive from Springfield to St. Louis, leaving time for various detours and bits of sight-seeing.

The sight-seeing along Route 66 is not about spectacular scenic destinations, though there are a few of those further west. It is much more about the eccentricities of the road itself and those who built it, lived by it, and travelled it. There is, for instance, the original section of red brick pavement, now a country road requireing a detour off the modern route.

Then there is the concrete section, which is now a rural sideroad on the outskirts of Nilwood, Ilinois, where a turkey left tracks in the wet concrete that are still visible a hundred years later. This is a very small and eccentric site indeed. The small sign that marks the spot does not look like it was errected by the highway department, still less the folk-art turkey sculpture that stands at the foot of the sign. I can’t say for certain who erected that sign, but it does not look like an official highway marker, and the turkey certainly is not. I find them both symbolic of the eccentric public/private partnership that is the museum that is Route 66.

Speaking of eccentricity, we made a stop at Henry’s Rabbit Ranch. That is Rabbit as in Volkswagen, not rabbit as in bunny. There is no designated place to park. You sort of nudge your car in somewhere and hope it’s not in the way. For a roadside attraction aimed at passing roadies, this is somewhat strange. But it is part of the ordinary eccentricity of the road.

The Rabbit Ranch owner loves to tell his story: the ranch is a hobby that became an obsession. Some might call it hoarding. (Okay, I would call it hoarding.) But hoarding becomes a virtue, an exercise in ordinary eccentricity, if you put up a sign.

We bought a Bob Waldmire print for our artist daughter-in-law. The owner knew Bob Waldmire, who passed through many times before he died. He has Bob Waldmire’s old VW Rabbit that he used before the VW bus and school bus that we saw at the museum in Pontiac. The Rabbit is a station wagon with a wooden addition on the roof like the more ambitious one on the school bus. But there is none of the trinket accumulation or detailed annotation of the other vehicles. And here it is not being preserved, it is merely being kept.

That seems to be a recurring feature of the ordinary eccentricity of the road. While there are lots of laudable preservation efforts, sometimes it is just about keeping stuff. Preservation seems a sane and forward looking approach, but somehow more mundane than simply keeping things. Preservation corporatizes the experience. Keeping is more consonant with the ordinary eccentricity of the road.

I suppose this happy state cannot continue forever. At as certain point what is not preserved will be forgotten, abandoned, knocked down, or will simply fall to bits. We will be left only with the preserved and the restored, and that will be fine and lovely, but it won’t be the same.

This kept-not-preserved thing is repeated all along the road. It adds a sense of urgency to the trip. Any of this may be gone at any time. Ordinary eccentricity has no succession plan. When the current owner dies, no one would know how to keep the thing up. It is an extension of the personality of the eccentric and will become mere junk the moment the animating spirit departs. The preserved parts of the road are important too. But without the merely kept it would be less a living thing.

Of course, some of it is not even kept. It is simply abandoned and has not finished falling down yet. There is far too much of this to keep, let alone preserve. Will Route 66 be the same when places like Afton (later, in Oklahoma) finish falling down?

Seeking lunch on the approach to St Louis, we stopped at the Luna Café on Chain of Rocks road. It is authentic. “Authentic” is an American word meaning the roofline sags and it has not been painted in 30 years. It looks rough and Anna is hesitant to go in. But we are the only car in the lot (not a Harley in site!) and I am in a mood to go on all the rides on this trip, so in we go, our hands over our wallets. We are greeted cheerfully by the woman behind the bar who, eccentrically enough, does not tell us the entire history of the business (perhaps, she does not own it). The place is just a bar now so there is no lunch to be had. She asks if we want something to drink but is not in the least put out when we say no. Having no prospect of getting business out of us does not change her mood in the slightest. She invites us to take all the pictures we want. I get Anna to stand in front of various things while I take pictures of them.

I think it is here that I start to think of this project as “Anna standing in front of 100 things across America”. The name will not stick, but this business of taking pictures of oneself or loved ones standing in front of things is definitely a piece of contemporary ordinary eccentricity.

The barkeep directs us to the local lunch place, the Itty Bitty Café, a half mile back the way we came. The building is almost as authentic as the Luna Café, but loses one authenticity point for having been painted in recent memory. There is Route 66 memorabilia on the walls, some of it seemingly older than the road itself. There is also a second-rate folk-art Route 66 map that was painted on one wall long ago. But the place is clean and the staff are pleasant in the rural way of people just being who they are at work, instead of who they are trained to be, and talking about what interests them in the words they use at home instead of speaking out of the employee handbook.

Ordinary eccentricity again. Ordinary eccentricity, it seems, does not waste a lot of time and money on paint. Or fixing things. (Or rather, it either spends nothing or far more than is needed.)

The food is good in a local-hangout kind of way. I had a catfish sandwich and it was well cooked and delicious. But it is served on two pieces of plain bread out of the packet with one slice of lettuce, two slices of tomato and one of onion on the plate beside it. Presentation is not part of the product at the Itty Bitty Cafe, either in the building, the furniture, or the plumbing. It doesn’t need to be. We are the only customers who are not greeted by name – the only non-regulars. People who walk in to pick up phone orders are also greeted by name. They exchange bits of news. It is a busy place – a popular place. Customers gossip from table to table. This is a place where people meet people, not a place where customers meet brands. You can’t package this as a franchise. Nor, I suppose can you protect it or nurture it or encourage its development or preservation. It is a virtuous weed that can only grow in neglected ground. Prosperity is not without its downsides.

We get stuck at a red light to cross the one lane bridge that leads to the parking lot for the now closed Chain of Rocks Bridge. I stopped just short of the loop in the road that activates the light. After much waiting and holding up other people, I am instructed by a local.

There is only one other car in the lot at Chain of Rocks parking lot. The weather is hot but dry. You have to walk a long way out on the bridge before you can see the river, and since we know our hotel is going to be overlooking the Mississippi, we decide not to bother walking out that far. Apart from the bend in the middle and its period narrowness, it is an unremarkable-looking bridge. The significance is in what it meant, not what it is. It is not a feat to marvel at, unless you think about driving a truck across it, and meeting another truck in the middle. Bridges seem so routine now that it is hard to realize the enormous developmental significance the older ones had when they opened. Today a new bridge may take a few minutes off your commute. When bridges like Chain of Rocks were built, they took days off a journey.

We proceed towards downtown St Louis and the Gateway Arch. I hate driving in downtowns, especially in places where everything is twisted around a freeway and its on ramps. Everything comes at you far too fast and makes too little geographic sense, and the contrast between the speed of the native who knows how it all works and the visitor who does not is so great as to be terrifying and frustrating to both.

And boy is it noisy! All cities are noisy to one degree or another, but downtown St. Louis is particularly cacophonous. This is not helped by construction in front of the hotel, but no matter where we walk, we are surrounded by constant noise. I wear my noise cancelling earbuds the whole time. Don’t leave home without them.

We walk to the arch. The weather is really not so hot, and it is unusually dry for St. Louis, but we are not acclimatized. It feels hot to us, so we take it easy and don’t go far or fast.

The arch is a marvel, but there is not much to do with it. One can explore a church or a ruined abbey for hours, but the arch is so simple that by the time you have walked up to it, under it, and touched its steel flanks, you have pretty much exhausted the experience. (You can ride an elevator to the top, but we don’t because of our claustrophobia – besides our hotel room provides a 14th-story view of the river and the city, so the view from the arch would provide little advance on what we have.)

The arch may be eccentric, but there is nothing ordinary about it. We check it off the things-to-see list and move on.

We walk down to the Mississippi to look at it. Anna elects to skip the ceremonial dipping of the finger that she usually practices at each significant body of water we visit. The water does not look welcoming.

We see a large heavy chain embedded in the the asphalt of the road. Eccentric? Certainly not ordinary.

We eat ice cream and walk back through a park to check out the brew pub for which the hotel clerk gave us free beer tokens. Along the way we discover a public clock that is eccentric in more ways than one.

Also this, which feels too studied to be eccentric.

That evening, we walk back to the brew pub for supper. All they have on tap are different varieties of lager. Not an ale in sight. The waitress is not keen on several of the choices, but offers us samples. We confirm her opinion. One black lager, that she particularly disapproves of, tastes like it is trying to be Guinness and failing. As we continue west we will begin to wonder if there any ales west of the Mississippi. Falling back on Sam Adams is the safe choice when the American beer scene grows desolate. The food we ate has faded entirely from memory.

Despite the grand monument that is the Gateway Arch, of all the day’s sights, I think it is the red brick road and the turkey tracks that will stick with me longest. Ordinary eccentricity.